Hokkaido’s fine, dry powder — often called “JAPOW” — is famous among skiers worldwide. This article explains the climate, geography, and meteorology that combine to create Japan’s legendary powder snow, and why places like Niseko and Rusutsu offer such exceptional riding.

1. Cold Air, Low Humidity: The Basics of Hokkaido Powder

Compared with Japan’s main island (Honshu), Hokkaido is colder. Lower temperatures mean the air holds much less water vapor. When there is less moisture in the air, ice crystals don’t grow large — they remain small and fragile as they form. The result is a fine, dry, and incredibly light snow that we call powder.

Unlike wetter snow that becomes heavy and sticky, Hokkaido’s powder contains very little liquid water. If you pick it up with your hand it crumbles easily; under your skis it feels as if you’re floating. That “floating” sensation is precisely why so many riders come back year after year.

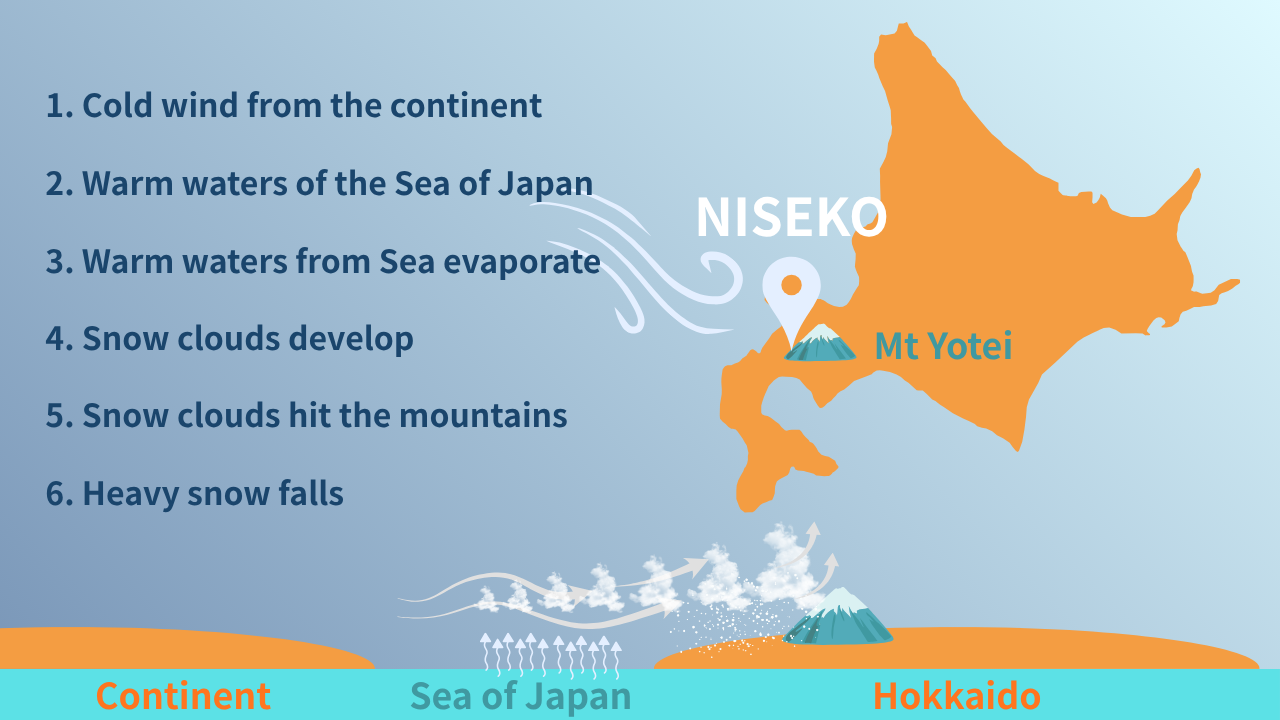

2. How the Sea and Siberian Winds Create Massive Snowfalls

The process starts over the Sea of Japan. The western side of Hokkaido faces waters warmed by a relatively warm current. Even in winter, the sea surface is warmer than the cold Siberian air blowing across it. When that frigid wind passes over the warmer sea, the air picks up moisture — much like steam rising off a bath — and forms heavily laden snow clouds.

As those moisture-rich clouds are pushed inland by the wind, they encounter coastal mountain ranges. The air is forced upward, cools, and dumps large amounts of snow on the sea-facing mountain slopes. This is called orographic snowfall or terrain-induced snowfall, and it is a key mechanism behind Hokkaido’s huge accumulations.

By the time the same cloud mass reaches the higher, inland ranges such as the Daisetsuzan mountains, it has already released much of its moisture. There, cold, dry air and low humidity favor the formation of extremely dry snow crystals — the kind of tiny, low-density flakes that make true powder skiing possible.

3. What Conditions Produce “Powder”?

Not all cold, snowy weather produces powder. A handful of specific meteorological conditions must come together:

- Cold temperatures (typically below −5°C): At these low temperatures water vapor solidifies into snow crystals without becoming liquid, producing dry flakes.

- Low humidity: Dry air prevents large, heavy crystals from forming and preserves fragile crystal structures.

- Continuous, stable snowfall: Regular new snow layers maintain a fresh, rideable surface rather than a consolidated crust.

When these elements align — as they regularly do in parts of Hokkaido — the conditions are perfect for extensive powder accumulations. Areas like Niseko, Furano, and Rusutsu are especially well-suited because their position relative to the Sea of Japan and local topography repeatedly create these ideal conditions.

4. Niseko: Why It’s Been Crowned a Powder Capital

Niseko’s reputation comes from both quantity and quality. The mountain receives prolific snowfall — sometimes totaling more than 15 meters across a winter — and most of that snow remains very dry. Because temperatures are consistently low, refreezing and crust formation are less common, so the powder stays soft and rideable longer.

In addition, Niseko sees almost daily fresh snow during peak months, creating a seemingly endless supply of new powder. Riders often describe the sensation as “floating” on the snow; the low snow density reduces friction and lets skis and boards glide smoothly. For many international visitors, that sensation defines the dream of skiing in Japan.

5. What Powder Feels Like — The Riding Experience

Powder’s appeal is both physical and emotional. Technically, low-density snow makes turns supple and forgiving: it cushions falls, absorbs speed, and allows riders to float through turns with minimal effort. Jumping and freestyle moves feel different in powder — landings are soft, and momentum is easier to preserve.

Visually and atmospherically, powder transforms the landscape. Fine, crystalline snow scatters light gently, creating soft highlights and a pristine, quiet environment. Riding through a snow-blanketed forest or down an untracked face feels almost meditative: the silence, the texture beneath your skis, and the soft spray of snow together form a deeply memorable winter experience.

6. Why Hokkaido Stands Out — Geography and Climate in Harmony

Hokkaido is unique because geography and climate reinforce each other. The warm current off the Sea of Japan supplies moisture; cold Siberian air provides the freezing temperatures needed to create dry crystals; mountains lift the moist air and trigger heavy snowfall. The repeated cycle of moisture pickup and orographic deposition is what makes certain Hokkaido ranges so consistently powdery.

Other areas in the world have great snow, but the combination of abundant moisture source, regular cold air outbreaks, and favorable mountain shapes is relatively rare. That’s why powder in Hokkaido is not just frequent — it’s exceptional.

7. Planning a Powder Trip — Timing and Expectations

If you’re chasing JAPOW, aim for the core winter months from January through February. February often delivers the deepest and most consistent powder — hence the nickname among some riders: “Japanuary.” Book early for accommodations and lessons during peak season, and consider local avalanche advisories and backcountry safety if you plan to venture off-piste.

Keep in mind that “powder” varies across regions: even within Hokkaido, microclimates and slope aspect change snow density, storm frequency, and wind effects. Visiting multiple resorts in one season is one of the best ways to compare conditions and find your personal favorite powder fields.